Written and photographed by David William Reeve

“The Closing of California’s Most Violent Juvenile Prison” depicts the Heman G. Stark Juvenile Prison, previously known as YTS or Youth Training School, as it stands today, years after it was closed by the State of California. My grandfather was a respected warden and consultant to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, including a stay as Associate Warden at Atlanta’s Federal Prison in the 1940’s. He served as a consultant at Stark for a brief time in the 1970’s.

It was my family connection that — after nine months of polite persistence — encouraged the State to issue permission for me to enter the property. My host this day, a Plant Manager, welcomed me by remarking, “Boy, you must be someone important ’cause request came from the top of the State of California to let you in.”

Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility was the youth division’s largest facility with a peak population of nearly 2,000 wards. Prisoners were called “wards” due to their young age.

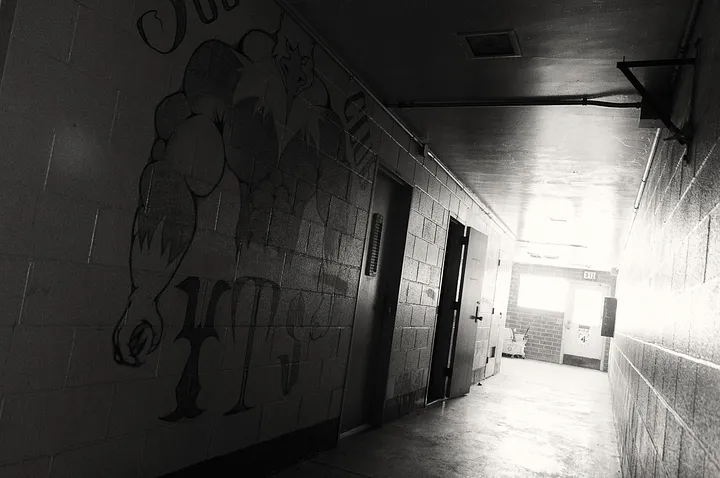

The prison held wards “as young as twelve” I was told, and was closed in 2010 due to persistent violence, “unsafe and unsatisfactory conditions”, and the murder of a prison counselor years earlier. It was known as “Gladiator School” for it’s unintended ability to harden young wards for what awaited them in men’s prison. Today, it’s a “warm” site, meaning it can be re-opened anytime.

A plant manager and his team provides basic maintenance, security, and oversight. For example, thieves will break in at night to steal the valuable copper pipes. The toilets could explode save for a chemical additive that breaks down the gasses in the pipes.

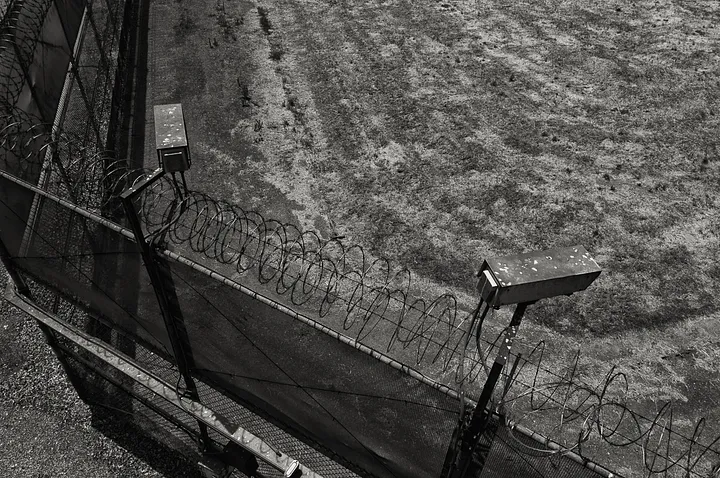

At any time, the Department of Juvenile Justice may call to revive the prison or a portion of it. Nearby Chino Men’s Prison (aka California Correctional Institution for Men, Chino) will use this space as temporary housing in the event of a riot or fire, as it did for 400 men in 2011.

These photos show the prison as it was in its last days, somewhat frozen in time… as if the prison was closed and everyone simply walked away.

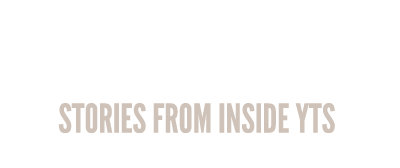

We used a master set of keys to enter a locked wooden door to the North East watchtower. Clearing cobwebs and crunching dead bugs under our boots, we passed an open, dry refrigerator and felt our way through the pitch darkness to a narrow stairway. The watchtower was remote from the rest of the prison campus and designed to be somewhat self sufficient for the guard on duty.

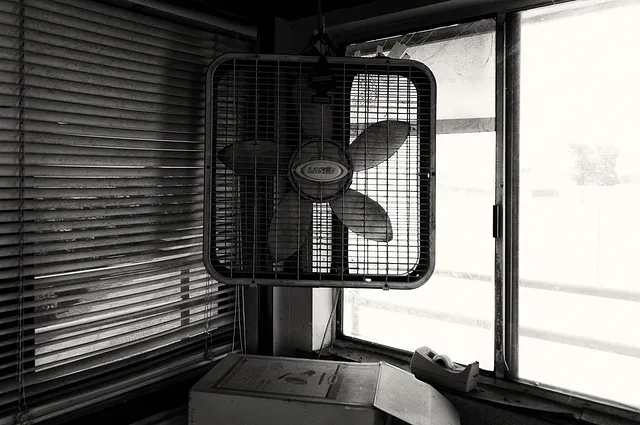

In addition to the refrigerator, there was a toilet positioned in such a way that the guard could maintain watch of the yard while sitting. A flyswatter and weathered broom indicated attempts at housekeeping while the hanging box fan told of hot afternoons under the blazing Chino sun, where summer temperatures would commonly reach 100 degrees or more.

No electricity this day. The whole prison was dark and eerie, aside from limited sunlight bleeding in through tarnished windows. Several times we were in complete darkness, just nothing. We felt the walls searching for doorknobs or a way out. Every door looks the same and in the dark, one could quickly lose track of the door you arrived from, or the door you may leave through.

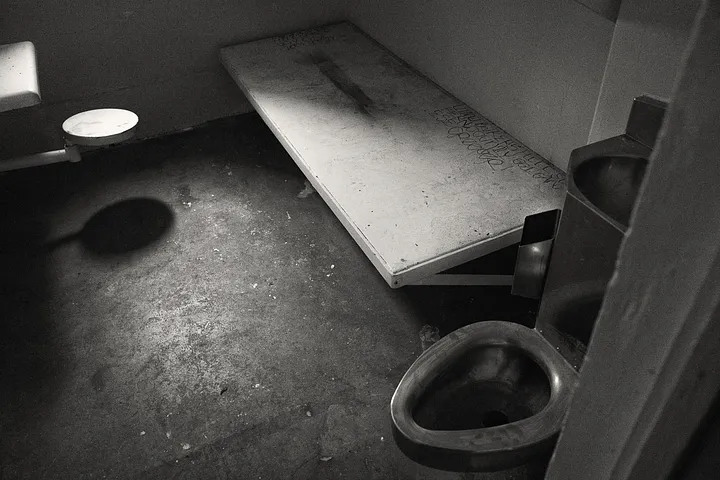

The prison has four housing units. Cells are about 8 x 6 feet and hold two bunk beds and a toilet. A report titled, “Special Review of High-Risk Issues at the Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility” from the Office of the Inspector General reported that more than half of the cells contained contraband: rope made of bed sheets, “pruno” (prison alcohol), a rolled-up mattress punching bag, tattoo devices, and containers used to hold bodily fluids that wards threw at staff (referred to as “gassing.”) The cell pictured held two wards. It was common for wards to spend 23 hours a day here, with one hour allowed for outdoor exercise. This practice — which the State reported as excessive — was referred to as “23 and 1 incarceration”.

Due to these conditions and more, State Judges opted to sentence youth offenders to county run prisons instead of Stark, which was run by the State. The feeling was that county youth correctional facilities were more progressive and offered rehabilitation opportunities that were successful in improving the lives of many.

Most rooms in the prison’s administrative buildings look as though someone started to cleanup, then abruptly stopped and never returned. This is the case in the picture above. An odd arrangement of photos tacked to a brick wall, a boxing trophy from 1987, a broom tucked under a sofa. The floor is covered in spider webs and thick with debris. This is the reception area where visitors would enter the prison.

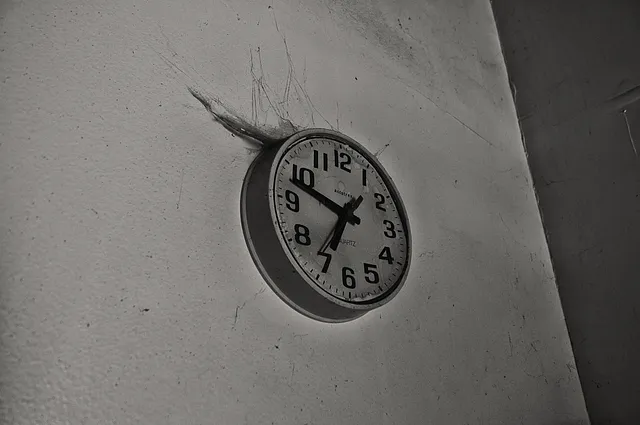

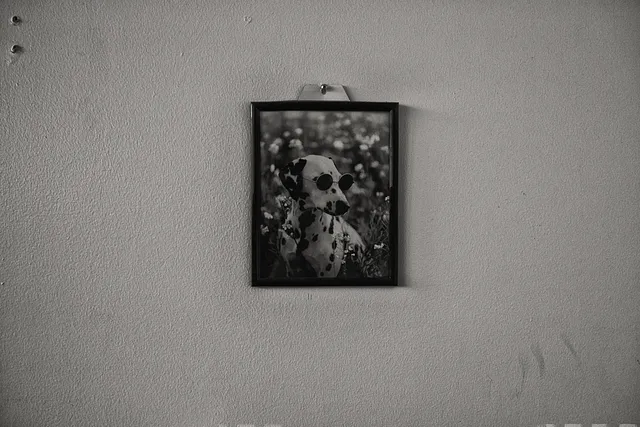

The prison was closed in 2010 when the State had no other solution for the violence and mayhem there; a State Attorney called it “an especially horrible place” and hundreds of workers lost their jobs. In the above photo, a calendar reads April 2010. There is an old Christmas card pinned to the board. A box of out-dated software containers was packed, but never stored away. A clock has stopped at 6:47 and spiders have nested. A framed photo of a Dalmatian wearing sunglasses hangs behind desk, perhaps indicating that one can work in this desperate place and still find a sense of humor.

After exploring the stillness of the administrative wing, my sense is that they just walked away.

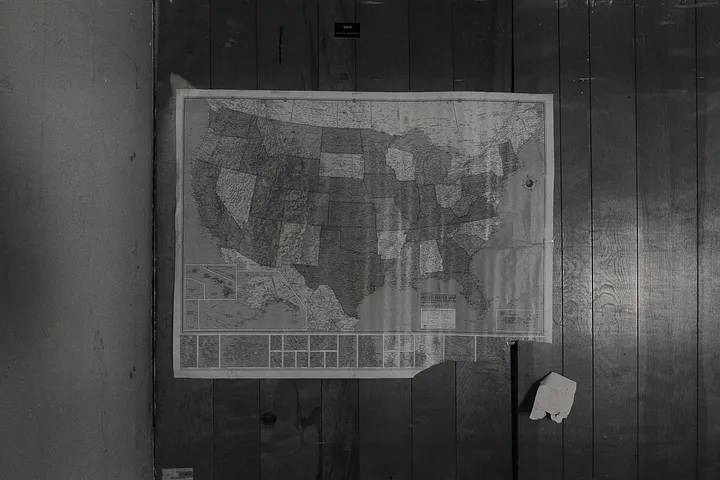

The nearby Chino Men’s Prison is out of frame, to the right of this photo of the northern fence. The two prisons are so close, in fact, that the men’s prison provided laundry services for the smaller juvenile prison. However, many wards preferred to launder their own clothes in their cells. This is because laundry sent to the men’s prison would often “be lost, returned discolored, or replaced with inferior clothing” — a game played by the inmates there.

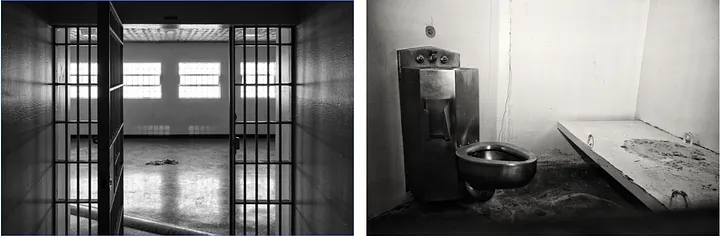

Each housing unit contains four isolation cells. These cells are smaller and cage-like, located behind a wall of bars, a steel door, and a chain link mesh wall. “This is where we kept the incorrigibles,” I was told.

At one time, there were ten fights a day reported here — commonly among rival gang members — and staff was unable to stop the violence. Wards would often commit offenses simply for the protection that isolation afforded them.

In addition to the basketball court (pictured above), the prison had a swimming pool, gymnasium, two football fields, boxing ring, and a weight room. The prison held competitive games of basketball in the gym under the team name, Stark Champs.

At one point in time, there were visiting teams from other prisons. Competitions were held in basketball, soccer, football, softball and boxing. This all ended after the murder of a correction officer which led to many changes.

There’s no privacy in prison. Shown above, the gymnasium toilet is located at the top of the bleachers in plain sight.

In the event that the prison becomes operational again, training by the San Bernardino Sheriff Department continues. The orange jumpsuit clad, tattooed, mannequin is used to practice handcuffing and takedown maneuvers in the gym.

The old handball court is now used for target practice. Sheriff Deputies practice riot control procedures by shooting beanbag rounds at this rough-hewn human-like target.

Stark Juvenile Prison included an accredited high school where attendance was mandatory for wards. Here they learned trade skills, worked on GEDs, and work assignments. Most feared going to school because they would be targeted with violence. Teachers entering segregation housing wore stab-proof vests and face masks that would prevent bodily fluid attacks from entering their mouth.

A visiting hall is pictured above. The seats collected in the center of the room may have been assembled for a group therapy class, religious studies, or in one documented case — a chance for privileged wards to play with visiting therapy animals (dogs or cats).

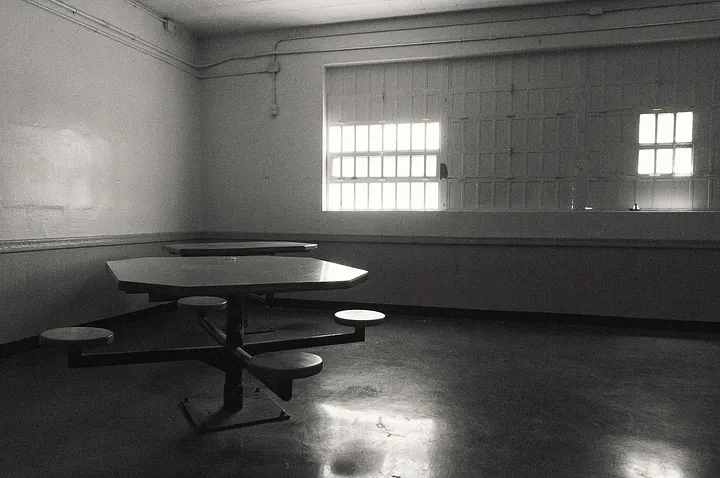

Dining tables sit no more than four wards on individual platform stools. This alternative to long benches and rectangular cafeteria-style tables was said to reduce violence by creating separation between wards and to prevent large crowds from congregating during meals. Wards were prevented from having a favorite seat and would be randomly assigned a stool before each meal.

A poem written on the chapel wall (below) reads:

Why us, I say to you.

I speak for the ones who are afraid

of what you do.

For there should be no fear in the

Land of Man.

We should all stand together,

Hand in hand.

Why do to others what you don’t

want done to you.

The answer to that questions lies

within the truth.

There is still a chance to stop

victimization but,

The only way we can do that is through global communication.

We must help our fellow man, through the good and the bad.

— “Why Us” by L. Copeland

David William Reeve is a writer and photographer from Southern California who documents the lives of young people at risk.

Contact: davidwilliamreeve (at) gmail (dot) com