Gladiator School: Stories from Inside YTS (Episode 20)

Edited and photographed by David William Reeve

Editor’s note: This is Part 20 of “Gladiator School: Stories from Inside YTS” — an oral history of life inside California’s most notorious juvenile prison. Youth Training School (known formally as Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility) had a reputation for mayhem, violence and murder that earned it the name Gladiator School. It closed in 2010. Juveniles were hardened for survival at YTS, only to be returned to the streets.

Since publishing the story The Closing of California’s Most Violent Juvenile Prison, survivors of YTS have come forward to tell stories of daily life inside. This series relays and respects their stories: Juvie told by those who were there.

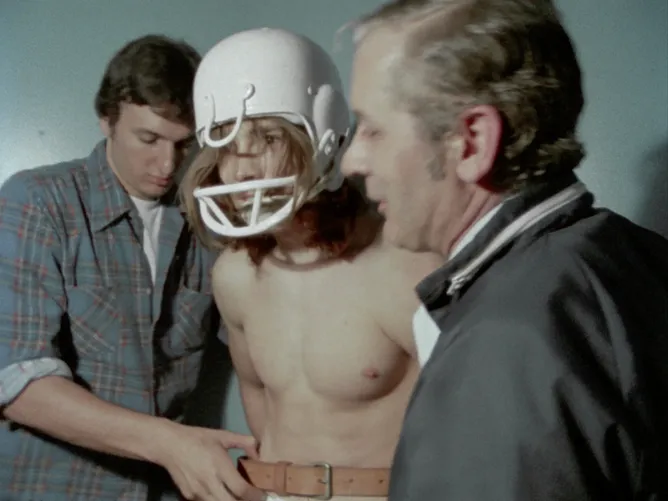

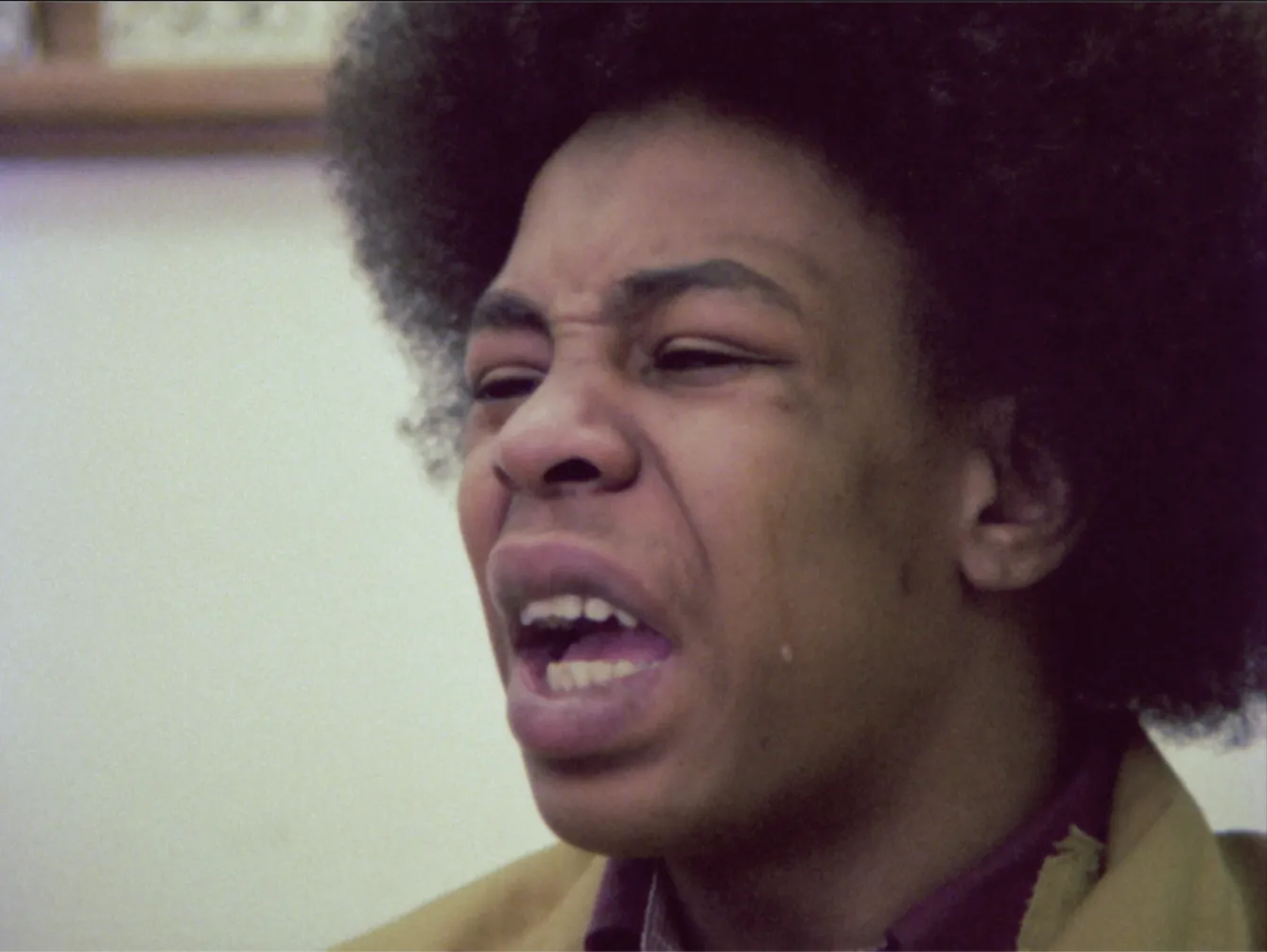

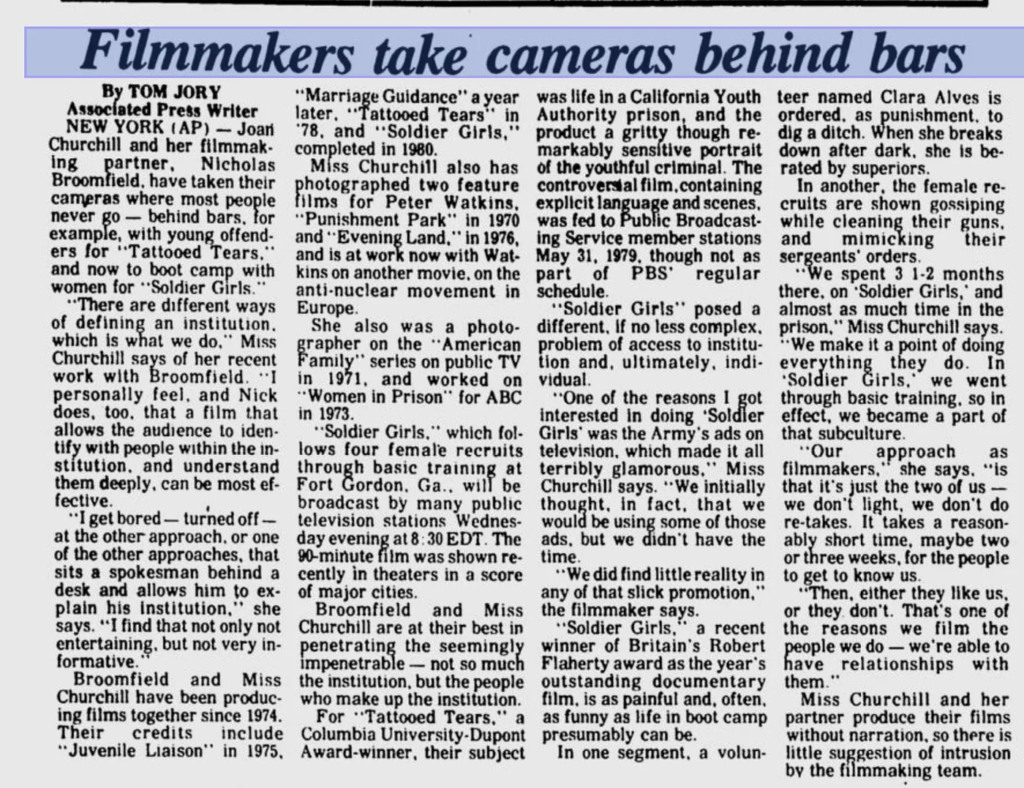

In this episode, Superintendent Keith Vermillion welcomes documentary filmmakers Nick Broomfield and Joan Churchill to YTS in 1978, eager to showcase the institution’s progressive programs. Given full access for 14 weeks, the filmmakers soon uncover a stark reality they hadn’t anticipated. As tensions rise, their camera captures young men in crisis, revealing an institution on the brink of violence.

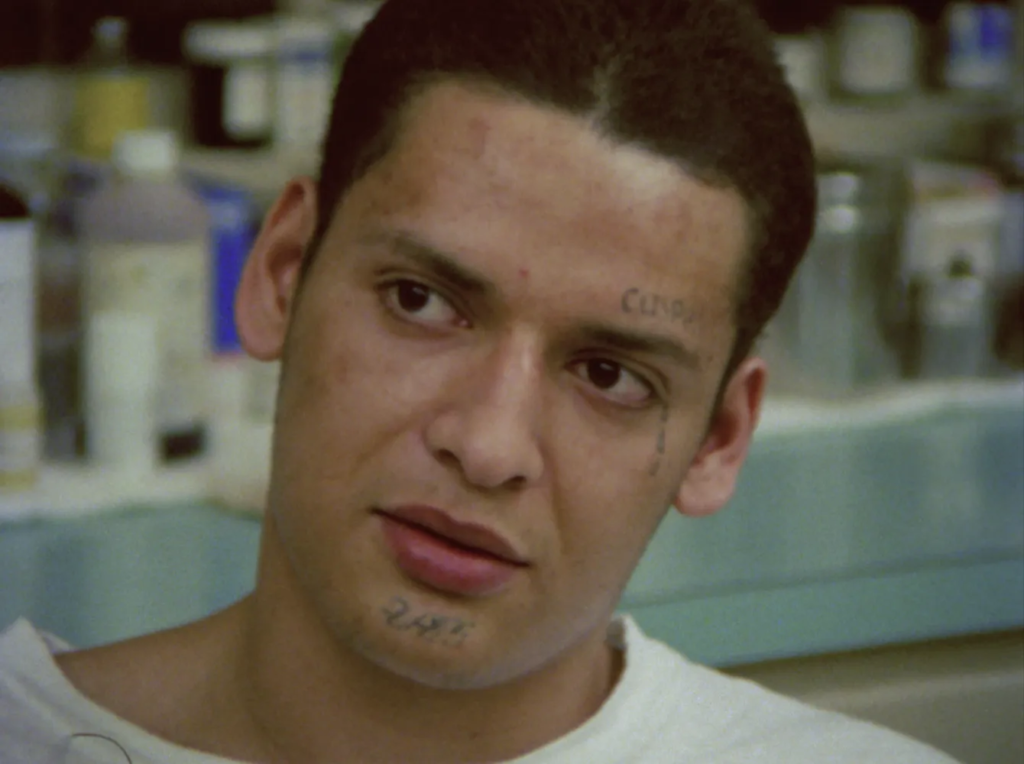

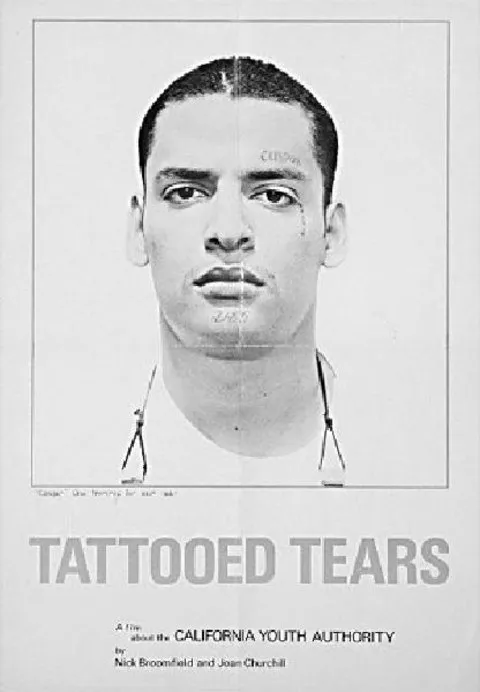

Tattooed Tears

(Joan Churchill) “The first film we did was about the police in the north of England. It was a film called Juvenile Liaison, where we spent 3 months in Blackburn, England, following a sergeant and two others — a policewoman and another constable who were spending their time going into schools and taking young children out who had been nicking apples and pencils from their classmates and treating them to horrific scenes, like taking a boy into a cell and saying, It’s dark in here at night and there’s no telly, and the kid is just quivering.”

“The police did not like that film, and they banned it. Except for one screening at the London Film Festival, the film was impossible to find and to see. That was when we decided we wanted to make films in America.”

“We were both living in England. My mother was an activist. Her name was Mae Churchill, and she knew a man in California who was the head of the juvenile prison system. He was a very decent guy, and I have no recollection of his name. My mother knew this man and was interested in giving us access and letting the film happen. Then, we had to talk our way into YTS with the Superintendent, Keith Vermillion.”

(Nick Broomfield) “He was pretty open to the idea. He was quite proud of some of their programs and that they had the trade line area. They were teaching them things.”

“There was a barbaric sense of humor there. It wasn’t the politically correct time that we’re in now. People would tell pretty grisly jokes and find them funny. Now it’d be impossible to have made the film we did.”

“They were very unbelievably trusting. To give us the keys and the panic buttons is pretty amazing…Basically, we wore an alarm that we could set off and indicate where we were in the institution, and then the security squad would come and get us out.”

(Joan) “In the beginning, we had to go around the whole institution and get everyone to sign release forms. I remember that ordeal, printing out thousands of release forms, which was a way of meeting everybody.”

“We were staying nearby in somebody’s horse ranch. I remember driving down this dirt gravel road late at night, and we had a ’55 Chevy that we bought on the budget for our transportation. We would drive down, and you would see these tarantulas crossing the road. It was so creepy. We were brutalized by the experience of spending a lot of time there. We would try to run them over. Oh, they made a horrible noise.”

“But then we’d come back to YTS in the morning, and somebody had been stabbed in the eye, and we missed it, so we started spending the night at the institution.”

(Nick) “We stayed in the hospital.”

(Joan) “They were testosterone-raging, immature people. It just upped the ante so much that the sense of tension there and the feeling of violence about to happen at any second, around any corner, was just amazing. In fact, our mentor, Colin Young, who had been head of both the film schools that we went to, remarked when he saw the film. He said, “Why was your shooting so abrupt? And why were you doing these crash zooms and pans and…” Which I had never really considered. Then I realized, of course, it was because of how we were all feeling while we were there inside.”

(Nick) “We were there 14 weeks, but that was like every day. The screaming was like a zoo, and it was directed at us, too. I was called “Faggot Englander” because Joan would carry the camera, which is obviously a rather male-looking instrument. I would carry all the magazines for the camera, sound gear, film cans, and anything else we needed in a supermarket trolley. I was Faggot Englander with the supermarket trolley.”

(Joan) “And his English accent didn’t help.”

(Nick) “That was initiation by fire, and no one understood what I was saying anyway.”

(Joan) “We had pretty much free-range, and we could go anywhere.”

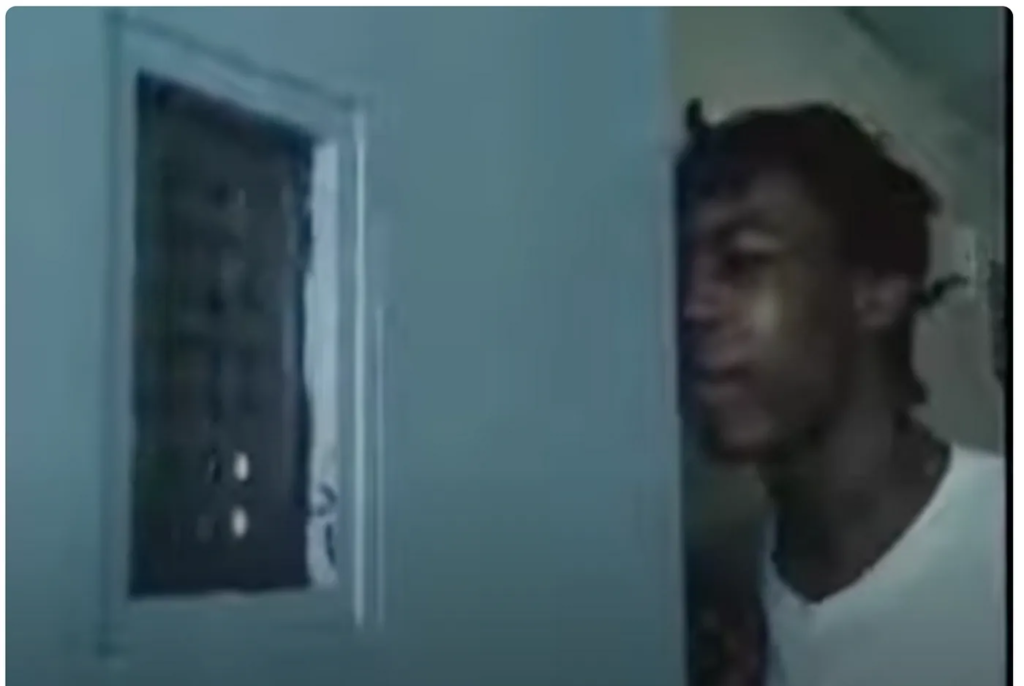

“We discovered people along the way. It would often be just walking by and somebody yelling through the crack in the door, “Hey,” and we would start talking to them. The opening scene with Cosmo, one of our favorite people there, is when Cosmo just starts having that conversation with that guy in the cell who had murdered his mother. We were there because we were filming Cosmo, and we knew he was going to be one of our main characters, and this conversation happened. At the beginning, this guy didn’t even know that we were there because what he could see was very limited until I went in through the grill there with the camera.”

(Nick) “I think the whole fear of the gangs, street gangs, and reprisal killings in the institution was a concern. A lot of the officers were frightened that people would get their home addresses and gangs from the hood would come and get sort of reprisals from them. That was a real fear. I remember they were starting all that talk about gang training, which was one of the few things we weren’t allowed to attend.”

(Joan) “They were very secretive about it. That was something they didn’t want us to film.”

(Nick) “Often, something would happen in Compton or elsewhere between rival gangs, and then something would happen in the institution. That was the undercurrent of real menacing violence. It wasn’t a logical place anymore.”

(Joan) “The teaching staff was quite welcoming. Remember the African-American gentleman? The man who was, I don’t know, like the boss of the staff. His name was Jerry. He was so sweet, really kind, and concerned.”

(Nick) “I think he had come up through the institution. He’d been at other schools on the way, hadn’t he? He was very committed to teaching and learning.”

(Joan) “And rehabilitation. The social worker was quite wonderful.”

(Nick) “They used to be able to smash the meal trays up and there was metal in the trays. They used to use that metal to make shanks.”

(Joan) That whole takedown of Marcus Hinojosa — he was the guy that they actually accused of taking the metal from the tray and then swallowing it. In fact his family got in touch with me. He had died (4–5 years ago).”

(Nick) “I think there was certainly violence in the institution.”

(Joan) “Totally, yeah. That’s why we were trying to spend the night.”

(Joan) “I think it was Sunday night. I don’t know if they made steak for everybody, but on the weekends, we got better food. After dinner, the staff who were going to be spending the night would take turns going into the kitchen, walking into this big walk-in refrigerator, and bringing back food for the rest of the staff. One night, it was my turn. I went down into the kitchen, and I was in this freezer looking for the steak or something.”

“One of the wards came in, and he was somebody I knew and liked. He was hoping that I would lie down with him. I just knew that I wasn’t going to be cooperating with him and that I needed to get out of there. I didn’t feel physically at threat, but it was getting to a point where I just needed to get out of there. I just said something, like, “Are you threatening me?” He was very close to me, and he just went like, “No, no, no!” If a staff member puts a report in that we were threatened by one of the wards, that was an automatic add-on to their sentence.”

“That’s when I just got out of there.”

(Nick) “The institution was very divided up into the hardcore, and then there were some of the more benign offenders on other wings.”

(Joan) “Was it O & R that was the hardcore one? That was a scary place.”

(Nick) “There was a killing. The staff were frightened and were hiding in the control tower, and could see I was surrounded by these guys, who were kicking my ass, and the staff weren’t going to do anything. I guess they weren’t armed. I think some of the staff felt, You’re doing the film. We’re not going to go and get beaten up for you. I was just there, and I had my equipment, and they just formed a circle around me, which was pretty menacing.”

(Joan) “It was like kick-ball.”

(Nick) “Yeah.”

(Nick) “We shot more than 200 rolls of film in 14 weeks. Most of our films went to DuArt in New York for processing. The guy who ran DuArt was really into film, and he sent all the film to a place called Iron Mountain. We got all the negatives. We got all the outtakes. But Tattooed Tears was probably done here, in California, at CFI.”

(Joan) “The film was processed at CFI, Consolidated Film Industry. A big lab. It came to be known as Can’t Find It, CFI.

(Nick) “We didn’t put that rape scene in, did we? I don’t think we did. There was one of the wards was charged with rape, and his mother came. This one ward had raped this other ward. It was a bit of a normal story, probably. It was a defenseless kid. It was clear that the mother was beside herself with grief about this rape and everything. We filmed her and the boy, and it was obvious that it had happened.”

“The mother had come to support her son, who happened to be the one who was the guilty party. A lot of it was the mother not understanding what had gone on and then finding out. I think it was just a pretty grisly story. It’s quite obvious the son was lying.”

It was so dark and awful, we didn’t put it in.”

(Joan) “I think they were disappointed (in the film.)”

(Nick) “I think there was a feeling that they were doing well and that we had made a very negative portrait.”

(Joan) “I think probably the guy in Sacramento that we made our initial contact with, somebody that my mother put us in touch with, I think he approved of the film. But I think it was the local people like Keith Vermillion who were unhappy. We had gotten a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, so it was going to broadcast on PBS.”

(Nick) “They did use the film to change the sentencing procedures in the institution. I guess they changed the ability of the institution to give inmates longer sentences because there were young people who went in there for firing a BB gun and got three months. Then because they were slight and couldn’t defend themselves, they got into lots of lights, then they’d pick up another couple of years. They changed that.”

(Joan) “It won the California State Bar Award for Distinguished Reporting and the Dupont Columbia Award for Outstanding Journalism.”

(Nick) “I think it had 88 “motherfuckers” in it, didn’t it? They counted every single swear word in it. Then they had to bleep them all as they went through, especially in the Bible Belt.”

(Joan) They sent us a readout of all the bleeps, which at one point I found in the files. I should have framed it. I don’t know where it is anymore.”

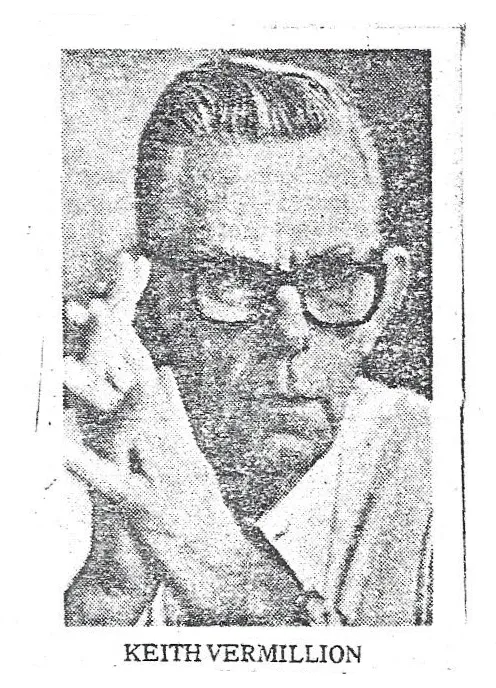

Nick Broomfield studied Law at Cardiff, Political Science at Essex, and Film at the National Film School under Professor Colin Young. His passion for photography began at 15 during a foreign exchange in France. While at university, he made his first film, Who Cares, using a borrowed camera.

Encouraged by Colin Young, he embraced participant observation and collaborated with Joan Churchill on films like Juvenile Liaison, Tattooed Tears, Soldier Girls, and Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer. Originally influenced by Fred Wiseman and others, he later developed his signature investigative style by inserting himself into Driving Me Crazy(1988), leading to a more experimental approach in films like Kurt & Courtney and Biggie & Tupac.

Broomfield has won numerous awards, including the Sundance First Prize, British Academy Award, Prix Italia, and Peabody Award.

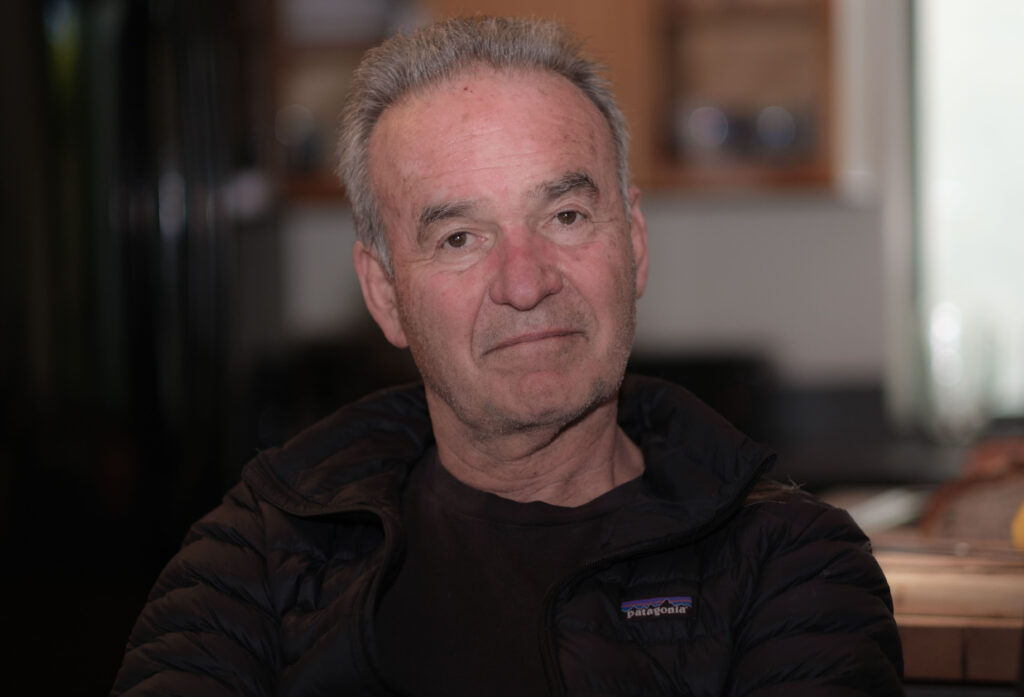

Joan Churchill is a pioneering filmmaker and cinematographer known for iconic music films like Gimme Shelter, No Nukes, and Jimi Plays Berkeley. She contributed to groundbreaking documentaries such as An American Family, Punishment Park, and Pumping Iron.

A frequent collaborator with Nick Broomfield, she worked on Lily Tomlin, Aileen: Life & Death of a Serial Killer, Kurt & Courtney, and Biggie & Tupac. Her work on Soldier Girls earned her a BAFTA and the Sundance Grand Jury Prize.

With her partner Alan Barker, she has produced vérité series like The Residents and American High, as well as films on mental health, including Bedlam and Medicating Normal. She was the first documentary cinematographer inducted into the American Society of Cinematographers and received their inaugural Lifetime Documentary Award in 2025.

A respected mentor, Churchill has taught at UCLA, USC, and film schools worldwide. Her accolades include a BAFTA, DuPont Columbia Awards, the Prix Italia, and DOC NYC’s Visionary Award.

David William Reeve is an independent writer and photographer who documents the lives of juveniles at risk. Visit davidreeve.net for more.

Contact: davidwilliamreeve (at) gmail (dot) com