YA Babies: Stories from Inside California Youth Authority (Ep 1)

Edited and photographed by David William Reeve

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of “YA Babies: Stories from Inside California Youth Authority” — an oral history of life inside California’s notorious juvenile prison system. The California Youth Authority made up a series of juvenile prisons focused on education, treatment, and intervention. Male and female wards entered the Youth Authority as young as 14, inspiring the term “YA Babies.”

Since publishing the story The Closing of California’s Most Violent Juvenile Prison, YA babies have come forward to tell stories of daily life inside the YA. This series relays and respects their stories: CYA told by those who were there.

In this episode, Adam from Shelltown comes up in the hard streets of Southeast San Diego, where family, new and old, prepare him for a future in the YA. At 18, he heads north into enemy territory at Chad School — a relentless juvenile prison where northern gangs swarm, forming unfamiliar alliances, new weapons, and no warning shots.

Suitable for parole

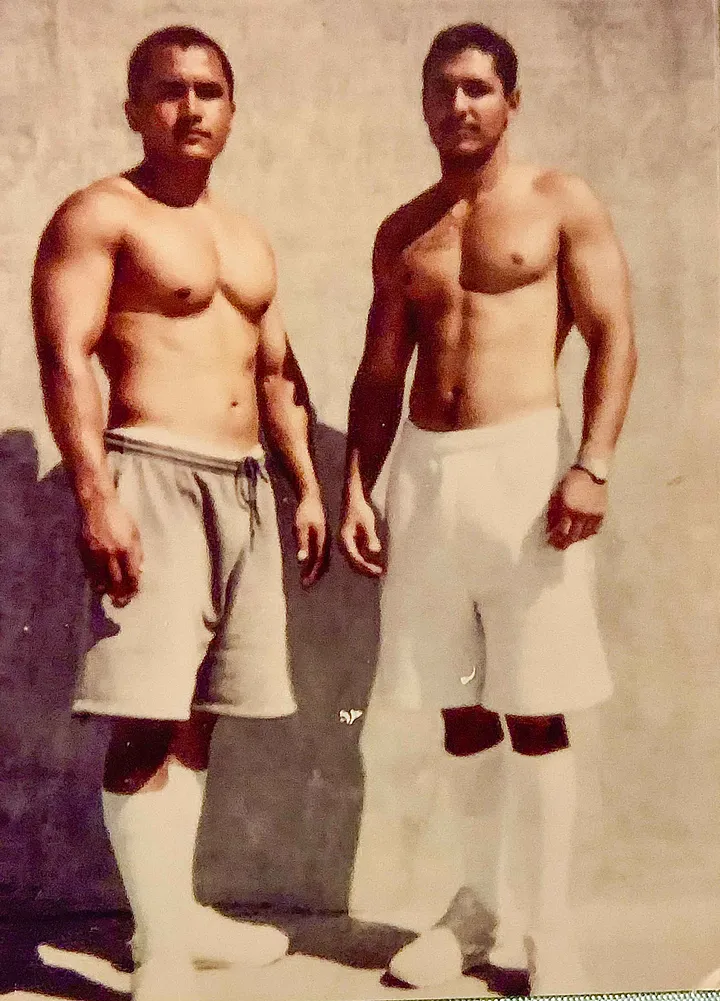

“I’m gonna teach you guys how to lift weights,” my uncle Willie said to me and my older brother in the backyard. He had been in and out of prison for four years. I was excited about my uncle teaching us to lift weights. After lifting weights for a little bit, he says, “…but I’m not here to just tell you how to lift weights. I’m here to school you on the rules of the streets, the rules of the game.”

“Don’t snitch on your homies. Don’t ever talk to the police.” He went on.

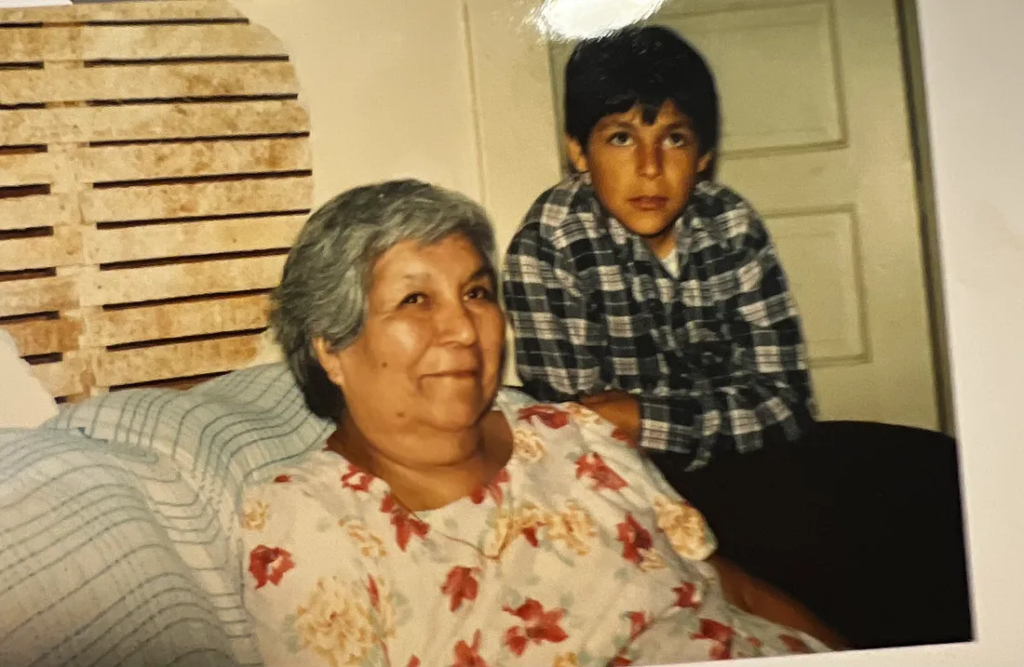

I was very young, first or second grade.

I didn’t think this information was relevant at my age, and I didn’t understand why he shared it with us. But later on, the path my life took, all of this information was relevant and served to guide me. Street life, crime, the system of juvenile halls, jails, prisons, the Youth Authority — you have to have some knowledge to navigate it, or you can become victimized by the system. I’m thankful that he shared it.

Growing up in Southeast San Diego, I experienced a lot of violence. My uncle Bobby, the angry one, the violent one, was the one who instilled the rage and the anger into me.

Bobby said, “When you let your anger out and unleash it on people, two things will happen. They’ll either become afraid of you, and they’re going to leave you alone. Or, you really hurt them, and they’ll leave you alone.” The goal was to be left alone, in the sense of not being bullied or picked on, because the community was rough.

I didn’t have enough. If you had something that I wanted, I’d take it from you. That was the mentality of the community that I grew up in. If someone could take something from me, they would, whether it’s jewelry off my body, a bicycle, whatever.

“Get off the bicycle! Give me your watch!”

I learned that if I had enough anger in me and someone messes with me, and I unleash it like a volcano, it will surprise them because they never suspected that to come out of a happy-looking little kid. If you’re violent, you display anger. People will leave you alone, or you’ll teach them to. Eventually, they’ll get it after you hurt them enough.

Growing up in a community where violence and poverty were an issue, I looked up to those who appeared to be safe and who appeared to have a lot.

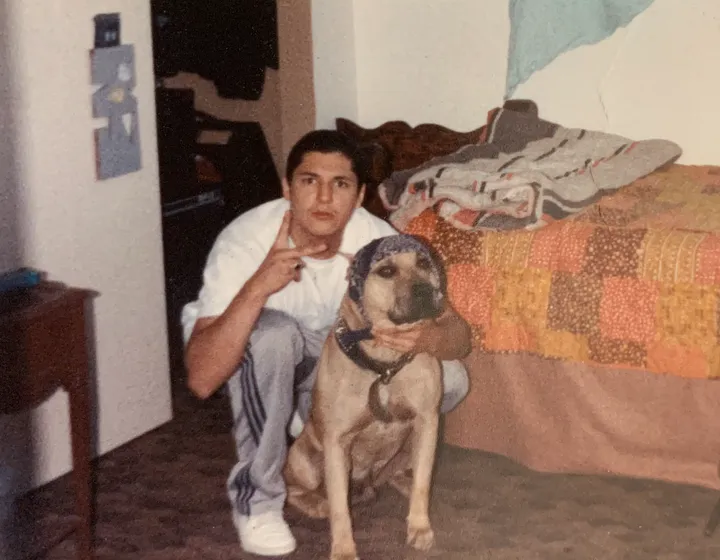

My brother was in the gang culture. The gang culture to me was them being supportive of one another. His older friends treated me like a little brother, and so I was embraced by them as well. I felt safe, accepted, cared for, and fed at times. I was invited over for dinner. Their moms would treat me like their own son. It was more than a gang. It was community, friendship, and acceptance. It was also the respect of our rivals.

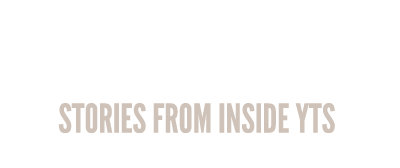

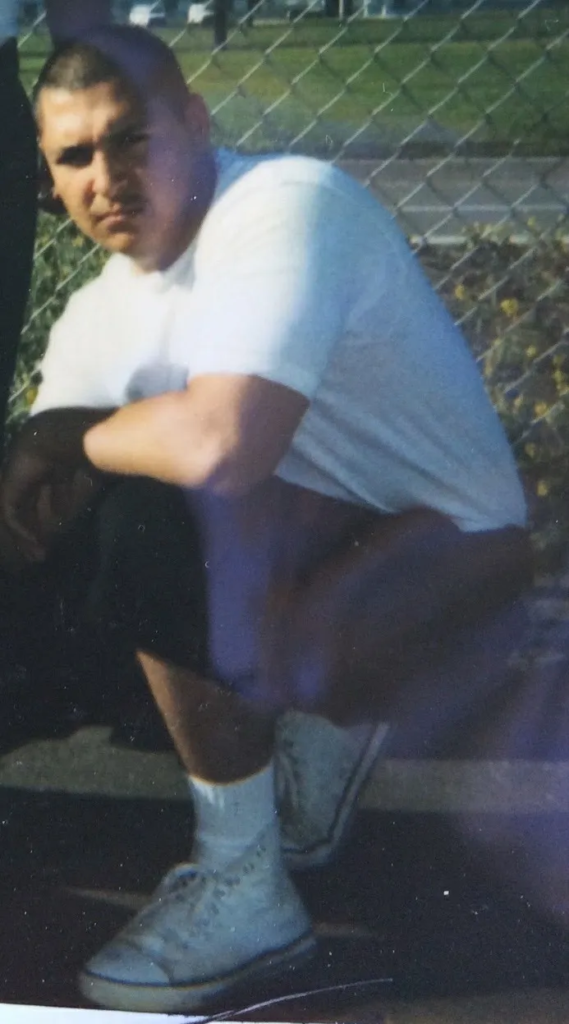

Southeast San Diego has many streets, but the neighborhood was Shelltown. The more I went out of my community, I started to see I was from that gang, and had to back it up with fights and getting assaulted. That progressed into getting arrested for graffiti at 13, marijuana at 14, more graffiti, under the influence at 15, and assault with a firearm at 16. At 16, I was violent. I carried a weapon. I slept with a gun. At 17, I was in and out of juvenile hall with multiple arrests. I was growing into a leader in my gang because most of the older people were in jail.

Then, I committed a gang-related murder when I was 17 and got arrested four months later.

I went through a 707 Fitness Transfer Hearing — a procedure to determine whether a juvenile could be tried as an adult, meaning you’re removed from the juvenile system and “transferred” to the adult system to serve your sentence. The other option was to be housed in a juvenile facility until your 25th birthday. Then you are sent to the adult system, which is State Prison, at 25. Children as young as 15 were being transferred to the adult system after all the “tough on crime” racist laws were implemented, as they were only applied to minority children.

Caucasian children did not experience 707 transfer hearings.

There was no real attempt to rehabilitate me. It was just a formality that affects mainly minorities. There was no counseling, no talking to a psychologist, no trauma assistance, nothing like that. Most don’t win it, so they end up in the adult system.

I lost the 707 Transfer Hearing because I could not be fixed under their system by the age of 25 and was convicted of second-degree murder.

When I went for sentencing, there was a law that stated that because I was a minor when I committed the crime, although I was 18 when I was being sentenced, I could be committed to the California Youth Authority. This means I would still be out of their jurisdiction by age 25. I went to the Youth Authority Southern Reception Center for a 90-day observation to determine if they could rehabilitate me. They sent a report to the sentencing judge saying I was amenable to all their programs. They could rehabilitate me by my 25th birthday — what juvenile hall said couldn’t be done.

The sentencing judge, Allan J. Preckle, said, This is a great report. It is good that they could rehabilitate you by your 25th birthday and that you’re amenable to all their programs. But seven years is not enough for what you’ve done. He goes, I’ll house you there, and when you turn 25, I’m committing you to the Department of Corrections.

My first awakening to the criminal justice system and the racism within it was to see how the poor and minorities are treated differently than others.

Most kids are appointed public defenders who work tirelessly to help juvenile clients. They represent them in the proceedings and navigate a hurt kid as a client, which can be challenging since most kids in these situations don’t trust anyone, especially if they have been hurt or felt betrayed by authorities. I believe kids need guidance, not more punishment.

Teaching kids about their trauma and why the hurt they’ve experienced causes them to view the world as unsafe and contributes to their bad decision-making and ultimately committing crimes.

People say that the system is flawed, but it isn’t flawed. The system is working perfectly the way it was intended to work. It wasn’t ever intended to fix people or to rehabilitate people. It was intended to punish and house. It’s a lot of economic value for the entire country by people being incarcerated for very long amounts of time.

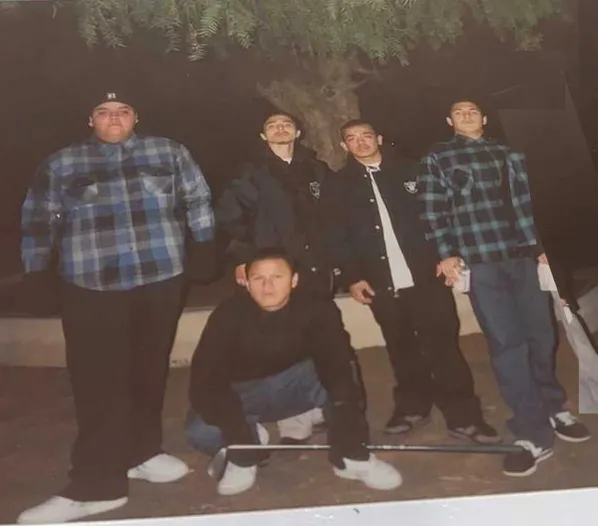

In the summer of ’92, after I was being sentenced, I asked them to send me to YTS. I had friends there, but it was closed to intake because it was full. I ended up going to Chad School in Stockton, which was a Northern California counterpart to YTS. It was 18 to 25-year-olds. It housed all the serious and violent murderers and robbers — people who were sentenced to prison but housed in the Youth Authority. Chad School had a Northern California population, which consisted of Northern Hispanic gang members, Central California Hispanic gang members, Crips and Bloods, and Bay Area Black gang members.

It just made for a different type of population where everybody was fighting groups against groups, gangs against gangs, factions against factions. You would have two groups team up and say, if this group starts trouble, we’ll team up to outnumber them. And this other group would say, Hey, we’re going to need a group to back us up to outnumber them. It’d become two groups against three groups, which was a lot of violence because 18 and 25-year-olds are strong, angry, full of rage, and capable of a lot of physical damage. If anything happens, it’ll be serious. It won’t just be a fistfight before the staff breaks it up. So that’s part of Gladiator School’s training; if you want to be safe, be more violent.

I still wanted to go to YTS because it was closer to home. It was probably an hour or two from home, as opposed to Stockton being 10 hours from home. I keep asking to get transferred. Whenever I have a six-month or four-month review, I say, “Transfer me! It’s closer to home!” I still had a lot of friends there. YTS was the place, really, for your reputation and your name.

I remember participating in many groups, but I don’t remember the groups ever addressing anything relevant to me, so I didn’t pay a lot of attention to them. I was just a body in the chair, signing in and signing out. There was a lot of manipulation, mind games, psychology, immature behaviors, and peer pressure. Looking back, it was horrible.

I got my first big tattoo in Chad. I had my city put on my back with ink that was purchased from one of the teachers. One of the staff helped us with some material for a tattoo gun. Contraband was tattoos, guitar strings for the needles, and Indian ink.

There were constant riots, but there were weapons involved. If you couldn’t get a knife, you would put large D batteries in socks and use it to hit people in the head, bruise them, or break their bones.

The weapon I had was manufactured. It was a piece of metal from a chain-link fence. I straightened it out, sharpened it, and connected it to something more solid. It was skinny but pretty big, like an ice pick.

I got caught up in the middle of a few riots in Chad. I was in class, and there was this rival gang. There were four of them, and I was by myself. My other two fellow gang members, my buddies, didn’t go to school that day. The four of them assaulted me.

We had a good little rumble for about four minutes. It took the officers a long time to get there. After that, I went and got my weapon. I was going to go back and stab them, and I got caught with it. That’s when I got kicked out of YA and sent to Tracy Reception Center.

There were four of us who got kicked out of the Youth Authority, and we got sent to Tracy. A sergeant took us out of the holding tank one at a time, stuffed us in a closet, and screamed at us.

We each got the same speech: You don’t belong here. You’re too young to be here. Anybody here that’s not 25 doesn’t belong here. You guys need to shut the fuck up. Don’t say shit. Keep your back to the wall. Respect everybody, and you’ll survive.

I knew it was true.

They’re like, “Fuck this guy,” the sergeant, “fuck his ass.”

I said, “No. He’s right.” I knew he was right. My perspective was different. I knew that it required more maturity and sophistication, and I knew I didn’t have it yet.

I immediately sensed the truth of what he said, but my own experience told me, I don’t belong here. I was 19. I didn’t belong there yet. My instincts told me I needed a good four more years before you could navigate this right. But I had to figure it out because I was already there.

We had shaved our heads bald. We were really targeting ourselves, making things worse, but we were representing the gangs and cities that we were from. The difference between the Youth Authority and prison was night and day.

In the Youth Authority, they would spray you with mace, slam you down, and handcuff you.

Prison guards had guns with bullets, and they’d shoot you. There were signs that read, “Warning. No warning shots inside,” meaning if you’re fighting, they’re shooting you.

I saw real violence like I’d never seen before. It was carnage right in front of me: metal on flesh, people stabbing each other, racial riots, officers shooting people, people getting carried out with bullet and stab wounds.

I saw one person getting stabbed on the ground, lying on his back. The guy was on top of him, stabbing him, and the officer shot. He ended up shooting the guy on the bottom by accident instead of shooting the guy on top doing the stabbing.

He got shot and stabbed. That was probably my first month, and I remember I was like, “Wow!”

There was no real discretion when they would shoot. They were just shooting to stop you. They didn’t care who they hit. I saw them hit the wrong people all the time. In prison, you can get shot for being near something. The sense of safety is completely gone.

That’s when I realized, when I was 24 to 26, the light started to turn on. I won’t get out of here if I don’t try. I can’t keep being this gangster. Then, I knew that I had to go through a process. I had to demonstrate something very different than what I demonstrated coming in.

Then, I went to level 3 at Centinela State Prison. I got a GED, took some vocational trades, and started going to sobriety groups and rehabilitative programs. It all had to be on paper, so I had to start involving myself, participating in things that would document and verify what I was doing, which got me on the rehabilitation path. I ended up in a level 3 for five years. Then, I went to a level 2 at Soledad State Prison in 1999 for 13 years. That’s more like a college of rehabilitative programs.

All the groups were led by us. We were teaching each other programs. There’d be some outside volunteers that would help. I was able to learn about trauma, root causes, and causative factors, which all came down to being in a safe, happy family.

My first parole hearing was in 2000 after being in nine years.

A parole hearing consists of getting to your causative factors, your childhood, and your life, and they ask what your influences were, what your family dynamic was, and if you ever suffered and were abused. They go into your family and social dynamic, the psychology of who you are. Then they talk about the commitment offense, the crime that you committed. They want to know how you became that person.

You have to describe to the parole commissioners how you went from a regular person at one time, a normal kid, to a person who developed character traits and characteristics, became a violent person, and practiced crime, whether it was robbery, assault, or murder. They want you to go into why you did what you did and what you are doing to unravel all that.

They want you to prepare a relapse prevention plan to show them that you won’t relapse into violence, drugs, alcohol, criminal mentality, or behavior.

Then, they go into what’s called your institutional behavior. They want to know what you have done in prison or jail. Have you gotten an education, GED, college degree, a vocational trade, marketable skill, work assignments? Have you been on time to work? What are your reports like? And programs — how many groups did you attend? How many groups did you complete? How many years did you do that?

There are groups for every issue under the sun. They want to know what you’ve done to address your violence, drug issues, anger, impulsivity, mental health, and substance abuse.

Lastly, they go into what’s called your parole plans. Where are you going to live? How are you going to support yourself? Where are you going to work?

I really believed that I was no longer a risk of “danger to society” the first time I went, and my record reflected that, but they just didn’t let me out. Ten years wasn’t enough for the crime that I committed. There were not a lot of what’s called “lifers” being found suitable for parole.

I went to five total parole hearings over 12 years. At the last parole hearing in 2012, I was finally found suitable for parole and deemed no longer a risk of danger to society. I have participated in no violence since 1993. I got 22 years of incarceration.

A lot of people in the yard asked me to help them prepare for their parole hearings, and I became overwhelmed with too many people asking me. I decided it would be a lot easier and more beneficial if I wrote down everything I knew and shared it on paper. I wrote a curriculum called the Parole Suitability Readiness Workshop; six lessons addressing how to prepare for parole.

I was able to teach it to five Inmate Facilitators and a group of 10 people. They, in turn, taught it to other people, and I was released from prison and paroled in 2013.

In 2013, I got a job washing dishes at a restaurant. Because of my experience in teaching parole, I was asked to speak to some youth in the projects in Los Angeles. I started sharing with this youth group and mentoring young gang members, juvenile gang members, and adults.

I got involved with another organization called Straightways, which taught career development skills to kids aging in the Foster Care System. In 2017, I went to work for the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, which had a contract with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to facilitate programs.

There was a new opportunity: seven former inmates who had a life term but were released either on parole or discharged parole would be selected to teach programs. I was chosen to be one of the initial seven. I taught the curriculum that I authored — the Parole Suitability Readiness Workshop.

I started working at Corcoran State Prison and Kern Valley State Prison teaching board prep class, its youth offender peer-to-peer mentoring program, and Criminals and Gang Members Anonymous.

I did that for a few years and got involved with reentry, helping people being released back into the community and connecting them with resources. In 2018, I spoke at the 36th Annual Juvenile Delinquency Law Training seminar. I was on a panel talking about my experiences as a juvenile in the juvenile system, and an attorney approached me after the conference and asked me to speak with one of her clients. This was the beginning of me becoming what’s known as an Independent Forensic Gang Expert.

I went to a program at Loyola Law School called the Independent Forensic Gang Expert College. I was taught how to be a gang expert using my knowledge and experience. What I would say about my participation in criminal proceedings, whether it’s juvenile or adult, is that I bring a perspective of gang culture and norms. It’s not necessarily geared for the defense or the prosecution. My role is to bring accurate gang culture.

The theory is that two gang members robbed a 7-Eleven, got the cash, and left. Because they’re both gang members, the prosecution would add a gang enhancement and say that these two men committed the robbery for the benefit promotion of the gang. It would add either 10 years or 25 years to life to the sentence. I’m called in and I’m asked, “Hey, was this crime gang-related?”

I review the evidence, talk to the person being charged with the crime, and determine whether the crime was gang-related.

There’s a lot of economic benefit in incarcerating little kids who misbehave because they don’t know how to express themselves when they’re hurting.

There was this little kid who was 14 years old. His parents lost him in the foster care system when he was five. He’s going to court. He’s in juvenile hall because he doesn’t behave in a group home. There’s no alternative discipline other than to put this little kid in jail.

He’s a participant in this big scheme. I see the scheme when a kid is in court, and there are 14 people assigned to him: social workers, psychologists, probation officers, counselors, mentors, attorneys, child advocate, educational supervisor for his individual education plan, judge, prosecutor, prosecutor’s assistant, law enforcement who arrested him — all these participants.

I tell this kid that a lot of people benefit every time you go to jail or court. They get jobs, and they’re assigned to you. What’s your benefit? What’s the benefit to you? He says nothing.

I tell him that the system is designed to have him in jail, to put him in there for as long as possible. If they were to release him, they’re going to release him with conditions that are almost impossible for kids to comply with because they’re impulsive and not very disciplined and orderly.

“My older brother was murdered. Every time I break a rule, they send me to juvenile hall,” he responded.

The system was teaching this kid that he was going to jail every time he broke a rule. For this minority child, jail was the only option the court, juvenile justice, or foster care system had for addressing misbehavior by preteens and adolescents.

We kept talking for 20 minutes, and then I went back and said, “Hey, you know what? I’m curious. I want to ask you why you are doing these things: fighting, stealing, doing drugs at such a young age.” He says, “My parents lost me in the foster care system when I was five, and they didn’t try to get me back.”

He knew what was going on, but no one asked him. So that’s the difference. When you’re interested in helping someone, you find out what’s wrong. When you want to punish them, you don’t ask. You just punish them. Look what they did.

I tell him that I could see what they’re trying to do.

“They’re setting you up so that they can try you as an adult later on in life,” I tell him. “They did the same thing to me.”

In the neighborhood, in the community, there are guys who fight, and there are guys who don’t want to fight, but they’ll fight anyway if you really make them. And there are guys who enjoy it. Then there are guys who have issues where fighting isn’t enough. They want to get a knife or a gun and finish it that way.

As a kid, I remember being happy and goofy. I like to joke around, make people laugh, be silly. My natural personality is upbeat and positive. But when I experienced all the stuff that I did — the trauma, victimization, poverty, domestic violence in the home, substance abuse in the home, violence in the community, police pulling you over daily and searching and accusing you of crimes you did not commit — it will obviously make you angry and bitter. Who-I-believe-I-am got buried in a bunch of pain, anger and confusion.

I got groomed into rage, anger, violence, gangs, substance abuse, reputation, wanting to hurt people — thinking that that was something to be admired. Hurting others, and people admiring you for that. Initially, it was to be safe. Then, when I saw the reaction of others, it became something much more distorted.

We are telling our children that although they have been hurt, with no one to protect them, our society does not value them enough to offer what is known as “care and treatment,” therapy — such as counseling and rehabilitative programs. We punish them and say they will never get out of prison because they did not know how to navigate the hurt they experienced.

Imagine someone who is not fully developed and has not yet become who they are, and they are sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

My goal now is to work with and help minority children who have experienced the same hurt, pain, and trauma that I did. They are at risk of being ushered into the juvenile justice system and the School-to-Prison Pipeline that minority children in California commonly experience.

One of the laws I am most proud to contribute to eliminates the sentencing of Life Without the Possibility of Parole, or LWOP, for juveniles.

Adam Mortera is the Founder and Executive Director of Juvenile Justice Advocates of California (JJAC). Previously, he had been incarcerated in San Diego Juvenile Hall, San Diego County Jail, California Youth Authority Southern Reception Center at Norwalk, Northern Reception Center at Sacramento, Chad in Stockton, Tracy Reception Center, Lancaster State Prison, Centinela State Prison, and Correctional Training Facility at Soledad.

Adam has both lived and professional experience in the Criminal Justice Field. His professional experience includes Legal Consultant, Gang/Prison Expert, Reintegration Case Manager- Flintridge Center, Life Coach/Inside Coordinator- Anti-Recidivism Coalition, Program Manager, Office Manager/Bookkeeper, and Owner/Chief Financial and Operating Officer for Rehab Building Company, Inc.

David William Reeve is an independent writer and photographer who documents the lives of juveniles at risk. Visit davidreeve.net for more.

Contact: davidwilliamreeve (at) gmail (dot) com