Gladiator School: Stories from Inside YTS (Episode 13)

Edited and photographed by David William Reeve

Editor’s note: This is Part 13 of “Gladiator School: Stories from Inside YTS” — an oral history of life inside California’s most notorious juvenile prison. Youth Training School (known formally as Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility) had a reputation for mayhem, violence and murder that earned it the name Gladiator School. It closed in 2010. Juveniles were hardened for survival at YTS, only to be returned to the streets.

Since publishing the story The Closing of California’s Most Violent Juvenile Prison, survivors of YTS have come forward to tell stories of daily life inside. This series relays and respects their stories: Juvie told by those who were there.

In this episode, Remigio “Mike” Chavez, is one of 11 sleeping on the floor of his family’s crowded, single-bedroom apartment in the Pico-Union neighborhood of Los Angeles —territory of the notorious 18th Street gang. He spends his days gazing from the apartment’s rooftop into the dream-like waters of a koi pond below. But as the dream fades, his nightmare begins, on a journey destined for YTS.

A white horse

“Welcome to the lodge – let’s sing!”

At YTS, they gave us a piece of land near the gym to build an ancient sweat lodge, where we would sweat and pray and vocalize the traditions of many tribes. The sweat lodge became the church for people who wanted to self-identify as Native Americans or as indigenous people from anywhere. There were brothers there who were very Black but had a little Cherokee in them. They identified themselves as that, and we accepted them. If you said you were Indian, we believed you.

I am a Yaqui Indian from Sonora, Mexico. I’ve always been very proud of being a native. I’m proud of my indigenous tattoos. Our race has always tattooed our faces to show loyalty and appreciation for the tribe. I started growing my hair long at YTS.

The sweat lodge was made out of a type of cedar that was hard and bendable. The lodge was covered and had a door, measured and built the way elders did it. It was like going to the doctor; you’d sweat from the steaming volcanic rocks. Sage was burning, and there were spiritual leaves. You could go there to talk about issues, meditate on the Lord, and sing. I finally got a taste of my spiritual side. I was able to hug brothers who were not from my gang.

We were there to feel what we wanted to feel. We went into the lodge with humbleness, on our knees. It was so hot, and I just wanted to get up and run, and when I couldn’t stand it anymore, I’d fall to the ground. I’d wonder if this is how Hell is.

I opened my eyes, and I saw a horse.

A white horse.

1979 Los Angeles.

I was a quiet kid.

“He doesn’t even talk, dawg,” the older homeboys would say.

These guys didn’t know that I had a stuttering problem, so I wouldn’t talk. I couldn’t talk. When I tried, I would stutter, and they would make fun of me, and I would attack these dudes.

We moved to Pico-Union apartments, behind Lucy’s Drive Thru, which was a stronghold for the 18th Street gangs around there. Gang members were everywhere around me — it was the thing to do.

I was 9 years old. I would be out on the street or at the liquor store looking at all these gang members. I would come home late at night, 2 or 3 in the morning, and my mother didn’t say, Where were you at? She’d say, Turn off the fucking light! They didn’t ask me where I was. It hurt. I wanted to be hugged; I wanted them to give a fuck. There were 11 of us in a one bedroom apartment. Some slept on the kitchen floor or the bathroom floor, and the rest in the hallway, but thank God we slept.

At the apartment, sometimes I didn’t know where my mom was at — she would would clean people’s homes to make money for us to eat. I just roamed the streets. But when the gang would knock on the door, I’d opened it, and they would bring me food.

I grew up into the gang. I started selling crack cocaine at 12 and had intimacy with an older woman. She was my mom’s friend, maybe 42. She would come looking for my mom when my mom wasn’t there, but I knew.

The older dudes would take me to expensive stores and buy me clothes. I learned at an early age to be loyal to them. It brought good things. I didn’t know how it would catch up to me or bond me to this place, but gang life has been a ladder that I fell from.

We moved to South Park in South Central LA, an area run by the Eastide Playboys gang — the rivals of 18th Street. I joined the Playboys, a normal gang with heavy structure behind it. I won’t tell you that I loved what we did, but there were things that we had to do, and I didn’t even know why it was being done, but I became a product of it, of my environment. I enjoyed it. It was nothing for me to be proud of.

These guys pulled up in a car and saw our bicycles. He looked at me and says,

“What are you doing here? Where are you from?”

I told them, “Playboys gang.”

“What do they call you?”

“They call me Duke Loco; I’m from Playboys,” I told them. “What’s up!”

“You got to get jumped in!”

Right then and there, they attacked me. But it wasn’t me; it was this entity that was in me already. The gang said I’m gonna destroy this kid, get him sent to prison…get him killed.

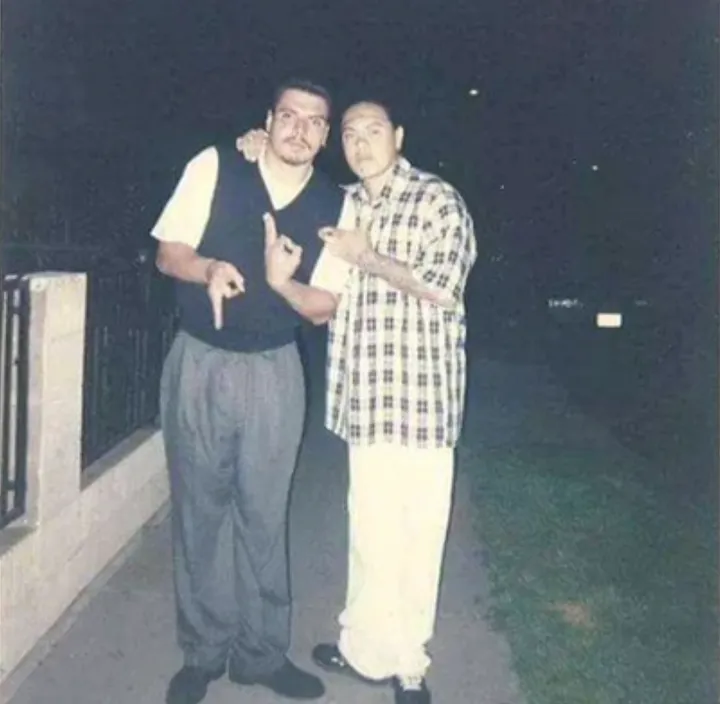

I was 12 years old when I first heard about YTS. One of my homeboys’ uncle and his brothers were there, and they had sent pictures. I saw these guys sharply dressed in group pictures from inside YTS.

“What prison are they at?” I asked. I had become familiar with the attire, the boots, the shirts. I didn’t ask what college or school they were at because it didn’t look like any school. My father was in jail in Mexico; my uncle too. Everybody in my family has had a little taste of the system. We drag our whole families into this. It becomes like a rope that we all put around each other. There is nothing good about prisons. It’s an atmosphere of despair, of evil. It’s coldness.

YTS was the heaviest reminder of what I was becoming and where I would end up for the rest of my life.

I got sentenced to 25 years to life for a gang-related murder. Another victim we practically ran over with a car. I got sent to do it. There was a meeting at the park, and they told us.

At the reception center at SRCC, they threw me into the cold room for fighting. It was an empty room with vents blowing cold air. I was in my boxers, shirt, and slippers. This is what they were doing to people who fight. After the first 3 hours, I couldn’t believe how cold it could get. They said I was going to be there for three days. I found the only spot in the room where the vent wasn’t blowing. It was down by the toilet. I balled up with my shirt pulled over my legs. By the third day, I was holding back tears, but they just came out. It was hard for me to understand how they’d leave me in there. It made me more arrogant for being in the cold room.

“I’ve been in the cold room,” I would say, “Have you been in there?”

It was only making me stronger in the sense that I someday knew that I wouldn’t be doing what I was doing in prison. I wasn’t going to be another statistic, someone who got out and OD’d.

I was 15 when I was sent to Nelles School in Whittier.

I got to YTS in 1990 and stayed for 7 years until I was 25.

There were rumors about the food being spit on and rat poison. The oatmeal was off limits, and so was the Jello. There were rules against eating it. It would mess with our heads because we were hungry. Sometimes dudes wouldn’t eat. There were accusations in the kitchen that would cause tension with the other races.

I was in Commercial Arts with a teacher named Tom Kieffer, who was a beautiful person. We called him Grandpa. He was the first white person I had interacted with. I only have love and admiration for that man. He loved us. He had so much patience with us. He showed us temperance, patience, and care. I took refuge there because I wanted to learn how to draw. I was trying to live by the pen and the pencil. I was drawing and doing good. I would draw cars and trade them for soups and coffee. I got a pair of Nike’s. I would draw a birthday card, a portrait. YTS had a lot of opportunities.

I saw dudes graduate from a pilot program with University of La Verne. I would see people graduating from computer classes. But they said I was a spoon, always stirring things up. I could have done more, but I was too busy with the gangs. The guards purposefully set us up to fight some dudes in the visiting area.

I went to the hole 7 times. Each time was 24 hours, then a 3-month program, then a 6-month program.

There was brotherhood in gang culture, but we’d see people break away. I think it took a lot of character for others to break away and go to school and get a diploma.

They used to have dances — I went to a few, but that all stopped when Ms. Baker was killed.

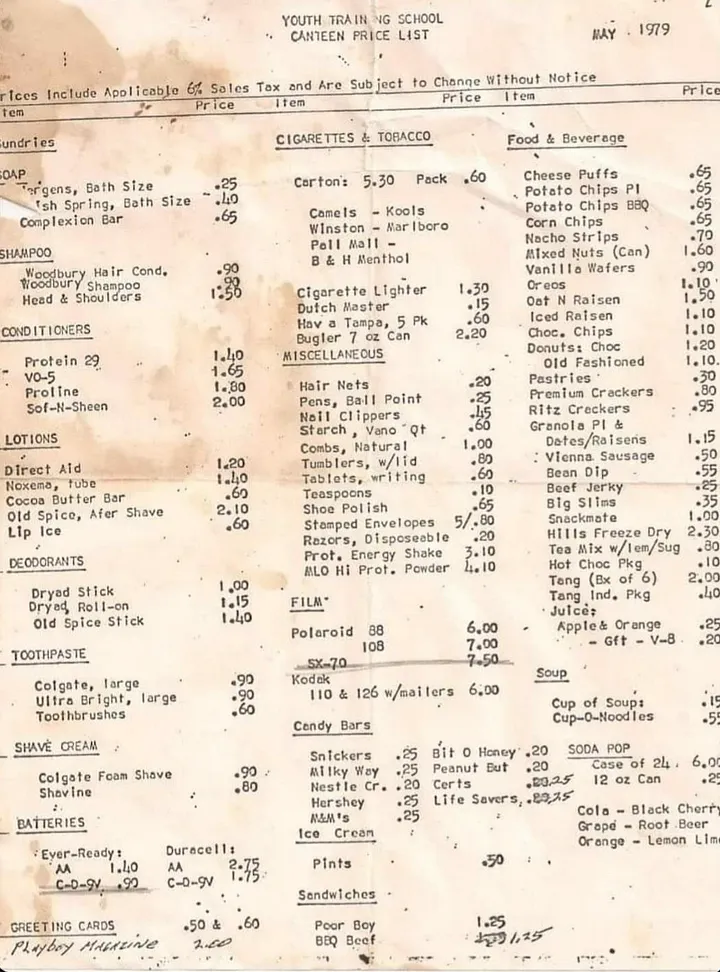

There was a marketplace for everything at YTS. They used to rent pornography. Some dude had a whole library collection of porn, renting out the books and selling them. Someone was selling coffee, trading soups for canteen money, dudes selling cups, and the motors for tattoos machines.

I told all the brothers to vote for my cellie and I for student council. This gave us access to open doors, hot water, and hot coffee. I got voted as Grievance Clerk, and my cellie was Student Council. We were allowed to go all over YTS, manipulating the system. We could go to the barbershop and library anytime; we were running amok with access to things that no one else could get access to.

My thing was coffee, 5 or 6 cups a day. I learned the many functions of coffee: the adrenaline of caffeine, it’s an anti-oxidant and it was good. Coffee and violence: if I didn’t have it, I’d be out there looking for it.

I ended up in the hole again for attacking some dude at trade. An enemy was there, and I had a key to a back room and attacked him there. I had already had two fights, so I was sent back to Chad.

“Get your stuff,” the guard said. It was 2000, and I was in the Los Angeles County Jail gang module, which was filled with nothing but murderers. All the men here were convicted of heavy crimes and gang affiliations or labeled a spoon and active member of Southern United Raza, like a lot of us were. Playboys were always labeled as a highly active gang. I really enjoyed being there because everybody that I grew up with was within the walled compound.

“Get your stuff!”

“I ain’t going nowhere; just let me know what’s happening.”

“You got bail, man; get your stuff.”

It’s hard to get bail from a gang module. It was God saying he wanted me to be out enjoying my life with my family.

Twelve days later, I got arrested again with a .380 in my pocket.

I saw the police cars, and the cops were looking at me. I turned around and started walking away, then running. I was going to toss the gun away, but it got caught in my waistband, and this police officer almost shot me.

“Get on the ground,” he shouted. As he was picking me up, his eyes were wide, and he was shaking — he must have been an angel — and he gives me a kiss. He gave me a kiss on my cheek!

“Thank God you got down on the ground,” he said. “I was about to kill you!”

Police officers don’t kiss people on the cheek. I didn’t understand it, but he was grateful that he didn’t kill me. It was God telling me that he wanted me for himself. I went back to the gang module two other times.

They eventually sent me to Pitchess North County Correctional Facility in Castaic — a SuperMax prison.

I got stabbed up real bad when I was in Corcoran Prison, stitches everywhere on my body. The cuts were infected, and it was a reminder that everyone in the system is accessible to whatever the system offers: death, despair, library books, a high school diploma, or write-ups and isolation.

I was in High Desert State Prison when they shot me to Centinela Prison to prepare to be deported. I never got the chance to see a judge. All my family is here.

After getting deported, I lived for a few years in a neighborhood called Olivar del Conde in Mixcoac, Mexico. I had opened up a tattoo shop and they were investigating me because I had become successful. I had a nice house and a business, and they didn’t want that. There is so much corruption there.

The police tortured me in Mexico, and cut my hair. They took my money and my watch. They thought all Yaqui natives were bad. I suffered — my human rights were violated. There is so much corruption there. It’s an evil place.

They tied my hands up with a chord from a phone charger and took me to an industrial park. I had a feeling that maybe my time was up. After they cut my hair, they used a measuring tape to measure me, they said, so they would know how deep to dig a hole and throw me in.

I encountered the Lord, and I would imagine what the Lord went through. They said to shut the fuck up about God. Some woman nearby saw me and took out her phone to call the Commander. One of the guys ate some food, and it made him sick. They untied my hands and told me to get the fuck out of there. I think it was the Lord that made that dude get sick.

It brought out that YTS person in me. That cold person. I would withstand anything like I was back in the hole at YTS eating cheese sandwiches.

Welcome to YTS! That’s what they would tell me. I was part of a system that, no matter what I did, that was it. Get used to it!

Swallow the food motherfucker!

They’d be there with the mace cans, threatening.

Always watching.

Nowhere to go, nowhere to run, just act.

“I want you to think of this as a theater,” my homeboy said, “where everyone is watching you!”

Everybody is watching you.

“I want you to go out there and perform,” he said. “This is YTS; this is where it all begins.”

I didn’t understand it. Maybe I was too innocent to even ask. I was just looking for that hug that I wasn’t gonna get, and I got another fight.

No soups, no coffee. Waiting for chow to come. Sometimes we’d be so hungry.

5 minutes to chow, 5 minutes to chow.

When I was deported to Mexico, I got a lawyer and came back to the United States a few years ago after winning my case, but there was an appeal.

I’d been to Pomona, Chino, Fontana, and West LA. I’ve seen YTS have an impact on the growing up, the growing old, and the growing dead — the systems of gangs — the Mexican, the Blacks, even the whites. I have some beautiful brothers here in Long Beach that are skinheads. There is an artist named Scribble who got out of YTS, overdosed, and died. I saw Asians and whites — some of my first white friends were from YTS. Good things happened. I was there with some good people. Who cares if they were gang members or drug addicts? They were people. They needed love. YTS wanted to diminish their love and take your love away if you’d allow it. It would make you think you’re this arrogant gangster.

I see my dad, and he says he’s so happy for me. He’s a mariachi and plays music in East LA. We talk, but before, we didn’t. My dad was absent my whole life in prison — I only saw him twice. It’s kind of hard to not feel shame when your kid is in prison for murder — it’s a disgrace to have a son in jail for murder. He’s proud of me for letting go of all that gang stuff.

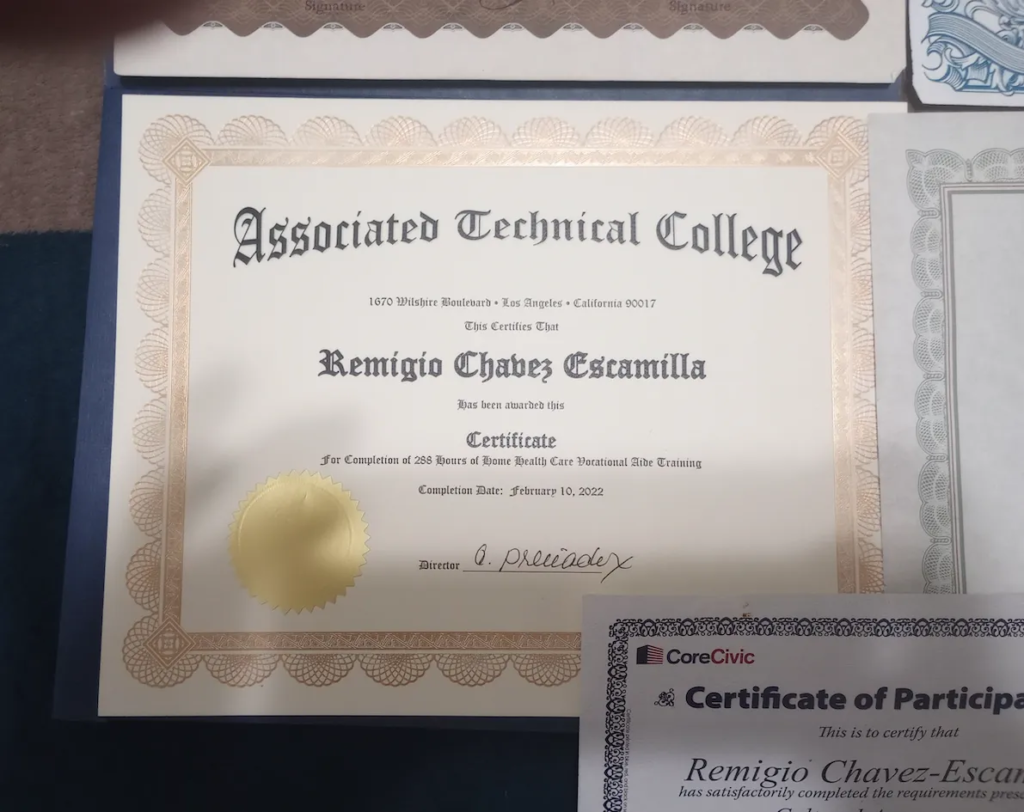

I’m 50 years old, and I’m healthy. I work. I went back to college and got certified in health care and CPR. I try to be kind to people, and to enjoy my life, however it comes. The beauty of life is not what you have or the clothes you wear. The beauty of life is being able to find your purpose.

Evil expands, searching for open doors. For 34 years, I’d never been out of prison for more than 6 months. I’ve been out for 2.5 years — the longest in my life. My life is an example of the route you shouldn’t take, the friends you shouldn’t have, and the things you shouldn’t do. Life can be so simple and beautiful. I thank God that I’m alive.

I remember that when we got to the Pico-Union apartments, I’d go up to the roof and look straight down. There was a pond with koi fish, and I’d look at these fishes for hours and hours.

And maybe I needed someone to be there — to tell me something — to tell me not to be on the roof all by myself, but there was no one there.

And I would go to the back side of the building, and there was nothing but gang members, weighing things and putting things into bags.

Then I would go on the other side of the building, and there were dudes inside a car, and they’d open the door of the car, and smoke would come out, and some chicks would come, but I wanted to go back and look at the fish.

It was like watching T.V., but we didn’t have a T.V. I had a show of fish, a show of gang members, gunshots, runnings and comings, and abandoned cars. I would look at the cars and look at the sky.

I was very curious — they’d say hyper — I didn’t know where all that wanting to know would lead me. It took me to places I didn’t want to know. I’d ask questions, and they’d tell me to shut up.

“What kind of car is that?”

It’s just a car!

“No, that car is different!”

They’re all the same. Just shut up!

I was very curious when I was growing up, and I thank God.

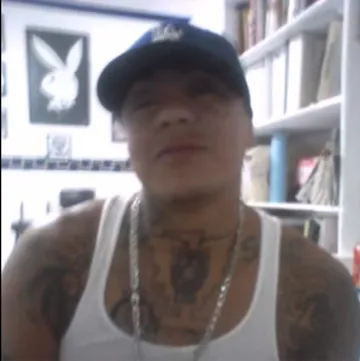

Remigio “Mike” Chavez aka Duke Loco at age 50 has spent half his life in the penal system, including stays at High Desert Prison, California State Prison at Corcoran, Centinela State Prison, Chino Institution for Men, Los Angeles County Jail, Pitchess North County Correctional Facility, Otay Mesa Detention Center, El Penal de San Jose El Alto, El Penal de San Juan del Rio, N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility (aka CHAD), SRCC, and Nelles School, including 7 years at YTS in Chino, California.

He was diagnosed with PTSD in 2021. In 2022, he enrolled at Associate Technical College where he graduated with honors. He holds a certificate in home healthcare and CPR, in addition to coursework in cultural awareness, creative writing, and poetry. He volunteers at Bread of Life Foursquare Church and is mentored by his pastors, Nancy and Ellen.

Mike is raising money and seeking donors to open a house where homeless men can get a shave, a shower, and a meal without the complexities of a shelter. He would like to hear from anyone who can help. (Contact davidwilliamreeve (at) gmail (dot) com with help)

Mike wishes to thank people who have helped him on his journey, including his mom and dad, Gilbert Chavez for visiting him when he felt forgotten, his teacher Dr. Castellanos, his employers Richard and Marcos at Beauchamp, and Uncle Robert John Funmaker.

Mike has three daughters who live in Mexico City.

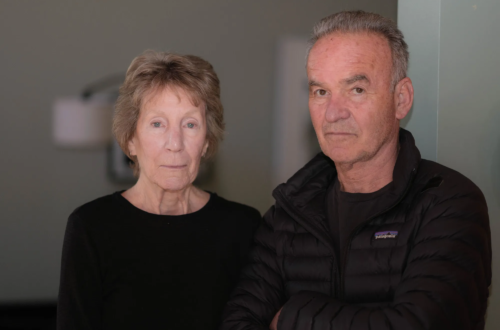

David William Reeve is an independent writer and photographer who documents the lives of juveniles at risk. Visit davidreeve.net for more.

Contact: davidwilliamreeve (at) gmail (dot) com